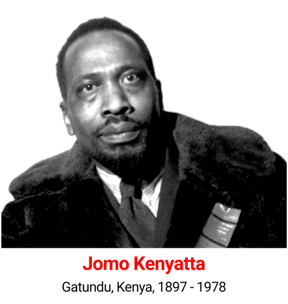

Jomo Kenyatta was born Kamau wa Moigoi in the heart of the Gikuyu country, north of Nairobi, at some point in the early 1890s. After the early death of his father, a minor chief, he was adopted by an uncle and soon thereafter moved in with his grandfather, a seer, and magician. After an illness brought him into contact with missionaries and their medicine, he ran away to the mission and undertook Western education. In 1914 he was baptized and soon took the Christian name Johnstone Kamau. At the same time, however, he underwent full adult initiation into his community, keeping one foot firmly in his indigenous culture. A carpenter, apprentice, and clerk during the later 1910s, Kenyatta became involved in the drive to reclaim Gikuyu lands from the Europeans in the 1920s. In those years, he began to be called Kenyatta, after the Swahili people's word for the kind of beaded belt he wore.

Johnstone Kenyatta and Bronislaw Malinowski did not meet each other by chance. Their ambitions were complementary, and they are said to have enjoyed an immediate rapport. By December 1934, Kenyatta had already lived in London for a long time and been on several trips around Europe. Malinowski, meanwhile, had just returned from a three-month trip that he had finally been able to organize in South and East Africa. He gained a cultured informant who could enlighten him on the controversy surrounding female circumcision among the Kikuyu, and Kenyatta, a professor to supervise him on a university degree about his people, whom he wished to make more widely known. With a scholarship that Malinowski secured for him from the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures, Johnstone was able to continue his studies and, at the end of 1937, defend his thesis in anthropology. It is not clear when Kenyatta first started using the name Jomo, although his friend Peter Mbiyu Koinange claimed that it was invented by the two of them for the publication of Kenyatta's book Facing Mount Kenya in 1938.

On his return to Kenya in 1946, Kenyatta immediately became a central figure in independence politics. Colonial administrators imprisoned him for seven years over his role—never fully elucidated—in the Mau Mau affair of 1952–59. Paradoxically, Kenyatta’s fourteen years in London and his seven in a hard-labor camp protected him from reputational damage in the kaleidoscopic shifts of Kenyan politics, so he emerged from prison in August 1961 to a hero’s welcome, understood by British and Africans alike as the probable leader of Kenya’s future. He was prime minister on Kenya’s independence in 1963 and president from 1964 until his death in 1978, when he was well into his eighties.

Facing Mount Kenya is a magnificent achievement, both as social science and as a special pleading. Malinowski saw this all from the start: “As a first-hand account of a representative African culture, as an invaluable document in the principles underlying culture-contact and change; last but not least, as a personal statement of the new outlook of a progressive African, this work will rank as a pioneering achievement of outstanding merit” (p. xiv, Preface, in Facing Mount Kenya).

Excerpts from:

CELARENT, B. (2010). Facing Mount Kenya by Jomo Kenyatta. American Journal of Sociology, 116(2): 722-728.

PEATRIK, A.–M. (2021). Jomo Kenyatta’s Facing Mount Kenya and its Rival Ethnographies: The Kikuyu in the Mirror of Colonial Anthropology, in Bérose - Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l'anthropologie, Paris.

Further reading:

ANGELO, A. (2019). Power and the Presidency in Kenya: The Jomo Kenyatta Years. New York, Cambridge University Press.

BERMAN, B. (1996). Ethnography as Politics, Politics as Ethnography: Kenyatta, Malinowski, and the Making of Facing Mount Kenya. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines, 30(3), 313–344. Online

FREDERIKSEN, B. (2008). Jomo Kenyatta, Marie Bonaparte and Bronislaw Malinowski on Clitoridectomy and Female Sexuality, History Workshop Journal, Volume 65, Issue 1, Spring 2008, Pages 23–48. Online

McFATE, M. (2018). Jomo Kenyatta, Louis Leakey, and the Counter-Insurgency System, in Military Anthropology: Soldiers, Scholars and Subjects at the Margins of Empire. London: Oxford University Press. Online

THROUP, David W. (2020). Jomo Kenyatta and the creation of the Kenyan state (1963–1978)', in Nic Cheeseman, Karuti Kanyinga, and Gabrielle Lynch (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Kenyan Politics. London: Oxford University Press. Online

Main publications:

1934. Kenya, in Nancy Cunard (org.), Negro Anthology. London: Wishart & co, p. 803-806. Online

1937. Kikuyu Religion, Ancestor-Worship, and Sacrificial Practices, Africa, 10 (3) p. 308-328. Online

1938/1978. Facing Mount Kenya, The Traditional Life of the Kikuyu. New York: Vintage Books. PDF

1942/1966. My People of Kikuyu and the Life of Chief Wangombe. London: Lutterworth Press.

1945. Kenya: the Land of conflict. London: Panaf Service.

1968. Suffering without Bitterness: The Founding of the Kenya Nation. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.